- Home

- Blair Braverman

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube Page 2

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube Read online

Page 2

A few days later, as I left the shop midafternoon, Arild called out to me. “Blair,” he said, “who do you think showers more often, me or Rune?”

“What?” I said.

“I think I shower more often,” he said, and hesitated. “By the way, if you’re interested in tasting whale, stop by here around six and you can try some. But if you’re busy, there’s no need. Just stop by if you feel like it, around six.”

When I came back at six he was closing up the shop, pulling silver foil over the meats and locking the front door. “You’re here,” he said. “Come up.” From the back room of the shop, we climbed a narrow flight of stairs to his second-story apartment. With the exception of the kitchen, and a rocking chair before the TV, most of the apartment seemed not to have been touched in years, or maybe decades; the lace-draped side tables and grandmotherly couches gave the distinct impression of being unused. A baby doll in a hand-embroidered dress, perched on the mantel, was fuzzy with dust. Arild glanced around, as if just noticing his surroundings. His wife, Anne Lill, he explained, lived in the larger house next door.

The kitchen counter was covered with cutting boards and bowls. A pan on the stove bubbled with gravy, and another with disks of black meat and caramelized onions in a pool of butter. From the oven Arild pulled a baking sheet lined with sliced potatoes.

“I enjoy cooking,” Arild remarked, moving a cutting board to the sink. “But I have to cook for myself. Anne Lill is always on a diet.”

He took a plate from the cabinet and arranged it with meat and potatoes, drizzling the gravy in an artful spiral, then looked over at me. “Get a plate,” he said. “What, city-pia, you think I’ll fill your plate for you? They’re in there.” I filled my plate and followed him down a hallway and out onto a roof patio. There was a table set up with two chairs, a white tablecloth, and a pitcher of milk. Arild sat down and started eating.

Though I enjoyed the company of the men at the table, and found their attention flattering, it was different to be here alone with Arild. On the patio, with a slight breeze and the faint calling of seagulls, above the now-empty shop, the meal felt oddly significant—a first date, loaded with expectation. But maybe, I told myself, the expectation was mine. A projection, or paranoia. So far everything seemed okay. Besides, I was hungry, having subsisted mostly on bread and ice cream since arriving in Mortenhals. I picked up my knife and sawed off a sliver of whale.

The meat was delicious, rich and crusty but giving way to a tender center. It was harder to get whale these days, Arild told me, after he finished chewing. It wasn’t long ago that whalers came through the fjord often, dragging minke whales up onto the beach at Sand. Big fat things, just enormous. Their bodies draped over the decks of ships with head and tail trailing in the water on either side. A dozen men could stand on a whale with pitchforks, cleaning it all at once. You could ride your horse down, strike a deal, and leave with a fifty-kilo strip of bone-free meat to last your family through winter. Whale had always been poor-man’s food. Now you had to know where to get it. Arild got this particular whale-beef from Lofoten—he’d heard rumors of it and sent down an order. He liked to do things the old way. In fact, he said, he had a showcase of sorts, a testament to the old ways, in the form of his family shop in its original building, just behind the barn. The Old Store was locked up, its windows boarded, but inside, the shop was exactly as it had once been, complete with shelves full of wares—a perfect time capsule from the 1950s. A museum? I asked, and he brushed off the question by taking a swallow of milk. “One has many plans,” he said.

We finished our food and ate second servings and then cut up strawberries and ate them with spoons in bowls of heavy cream. The strawberries were small and red and tasted almost too strongly of strawberry. It was because of the light, Arild said. Summer berries, they got sun all day and all night, and it changed them.

He led me inside and turned on the television, but when he saw that the news was about mass murderer Anders Breivik, he turned it off again. “Listen,” he said. He had to tell me something. He knew that Rune would invite me to a St. Hans’s bonfire on midsummer’s night, three days from now. There would be another man there, and I should be careful around him. That man was not harmless. Strange things happened on St. Hans’s night. I should be careful.

Feeling both relieved and disappointed that the evening was over, I thanked him for the food and the warning. “You can wash the dishes before you leave,” he said.

WHEN THE SALMON WAS HOT, Rune and I pulled it apart and ate the pieces with our fingers. Martin declined his fish and leaned over to vomit mucus on the ground.

“Something’s not right,” said Berit. She closed her eyes. “I have a terrible feeling.”

“Your Sami sense?” said Erling.

Berit nodded. “There’s something really bad here. A bad spirit.”

“Your Sami sense is sexy,” said Erling, after a while. He reached his hand into Berit’s pink leather crotch and began rubbing.

“Don’t shock the American,” said Berit.

I stood up and went closer to the fire. It was warm on my face, and my cheeks felt tight with the heat. Along the beach the other fires were dying out, but anyway they were unspectacular; the sky was bright as noon. In this northern summer, the sun drifting its slow laps around the sky, the longest day of the year wasn’t St. Hans’s. It was July.

“You’re cold?” said Rune. “I’ll keep you warm.” He put his arm around me. “I can always keep you warm.”

I had hoped he wouldn’t do this.

“Don’t be angry,” he said, “that I didn’t touch you until now.”

Behind us, Berit and Erling were making out. The children stood in the grass, throwing rocks at each other. Martin had slumped from his chair again and lay on his back, arms and legs spread, looking up at the blue sky. He was almost smiling.

I stepped away from Rune.

“You’re such a good girl,” he said. “When I win the lottery you can live with me. Here on Malangen. I’ll take such good care of you.” His head was low on his shoulders. “I’ll carve wood for you and give you everything you need.”

There were soft moans behind us, but I couldn’t tell whose they were. It was late, suddenly. All I wanted was to watch the fire.

Rune, his head somehow even lower, reached out one hand and patted me limply on the breast.

“I think I’ll go home now,” I said.

Martin lifted his head off the sand to watch me leave. “But, Blair,” he said in English. “The night is still young.”

CHAPTER ONE

I’VE SPENT MORE THAN HALF MY LIFE pointed northward, trying to answer private questions about violence and belonging and cold. By the time of my visit with Arild, I had come north—to Norway, to Alaska—again and again. I left once, too, and promised myself that I never had to go back. Arild would have liked that. “Six times she came, and once she left,” he could have told his customers, as if it was a riddle. He liked to make people wonder. He liked to know more than he said.

The seventh time I came north was because Arild invited me to turn his Old Store into a museum. After the summer was over, after I flew back home, after Martin was buried by the church on the hill:

I need a person to have the Old Store open on weekends during the summer, as I upon finishing work have no remaining energy to do it myself. If that sounds exciting you are wholeheartedly welcomed to work there (SMALL SALARY). As you know I have reasonable accommodations for you. Probably there will be no need to open every day and you can take walks in beautiful Malangen or borrow a car if that is what you prefer.

Since you wrote to me I understand that you have not been victim to one of the many shooting episodes at schools in the USA.

I wrote that I would arrive the next May. And so we slipped back into each other’s lives, out of convenience, out of necessity. The Old Store seemed like an excuse to keep asking my questions, a way to come back to Norway and face them head-on. I didn’t know th

at it was part of the answer.

On my first night back in Mortenhals, I hardly slept. Outside the window, in the bright gray sky, seagulls dipped and called all night, and I kept jolting awake, blinking against the light. Arild had given me a small bedroom above the front door of the shop, and its contents were unfamiliar: a table covered with jars of paintbrushes and shards of broken glass; a short orange bed with a mattress of rough-cut foam. Lying in the bed, my knees bent to fit, I felt comfortably blank. So here I was again. At one point I walked to the bathroom and looked out the window to see that the sheep had escaped from their pasture and lay in mounds around the diesel pump. I rubbed my eyes and went back to bed.

Midmorning I woke to murmured voices drifting through the floor. I made my way down the steep turquoise stairway, bracing my hands against the low ceiling to keep from tumbling forward, and came into the back of the shop. The air smelled like bacon from the flies that sizzled in the overhead lights. Arild and Rune sat at the table with a man they called He the Rich One. Arild glanced up from his newspaper, Northern Light, to pour me a cup of coffee. The front-page headline read, Never Again Getting a Foreign Tattoo.

“Do you remember she American girl from last year?” Arild asked He the Rich One. “She’s returned.”

“I’ve never seen the like,” said He the Rich One.

“I know,” said Arild. “She’s eating me out of my home.”

He the Rich One leaned forward on his elbows and gazed at me. He was large and tan with silver-brown hair combed straight back from his square face, the top four buttons of his shirt open to reveal a hairy brown chest. He’d made his fortune in slaughterhouses and sausage factories, and spent his winters tanning in Spain, surrounded by—he bragged—booze and ladies. He the Rich One had a house a few kilometers from Mortenhals, with running water and even a washing machine, but he called it a cabin. None of his neighbors had a problem with the washing machine. They had a problem with calling something a cabin when it was a house.

The people of Malangen were poor, but they lived, as they frequently and inaccurately reminded each other, in the richest country in the world, with a generous welfare system to boot. As such, their poverty was less about need than class, less about money than the facts that they were both northern and rural. Northern meant uncivilized. While southern Norwegians took pride in their restraint—they rarely made eye contact on the street, arrived precisely on time, and spoke a cosmopolitan dialect that resembled Danish—northerners were loose and vulgar. They cursed, slurred their words, joked often about death and sex, and gauged time loosely: “I’ll meet you Wednesday, after three cups of coffee.” Theirs was the Norway of witchcraft, storytelling, and incest, not minimalist furniture and the Nobel Peace Prize.

Rural meant long memories. How much had changed, really, since fifty years ago—or even a hundred—when the same families had lived on the same farms? The men of Malangen had been sealers and whalers, coming home from months on the Arctic Ocean with heaps of furs, baby polar bears to sell in Europe, and as much slimy, black sealmeat as their families could eat. They lined their skis with sealskin. They twined rope of walrus hide. They greased their saws with fish oil. They made liquor of birch sap and on the coldest winters they froze away the water to strengthen it. Women came to the peninsula to help with the haying, fell in love, married, and ran the farms when their husbands drowned at sea.

Then came electricity. Then came roads. Then came oil. Somewhere to the south, Brigitte Bardot raised a fuss and the seal-hunting industry collapsed, diminished to a single dark-gummed teenager selling flippers with his grandpa on a city dock. Men found other work: on oil rigs, in a factory that made Styrofoam boxes for exporting salmon, as cruise ship guides in the same waters where they had once hunted. The winters grew warmer, the summers longer. Forests spread over fields and up the mountains like a rising tide.

Everyone knew that He the Rich One was feeling wounded that year. He had owned a meat store in Storsteinnes, which was an hour’s drive away, and a big enough town to have a grocery store, a government liquor store, and a bank. He made his brother the manager. But another employee stole money from the register for months, until finally the store went bankrupt. Arild couldn’t believe that a person would be oblivious for that long about his own shop. That he wouldn’t notice. Not that Arild was complaining; he had his eye on the chest freezer that He the Rich One would be getting rid of.

“I understand why you want it,” He the Rich One said. “It’s jo a nicer freezer than you’ve ever had.”

Arild hummed. It wasn’t in his practice to contradict customers.

“It was a nicer shop than this, too,” said He the Rich One, turning to me. “Seven hundred square meters.” He looked sad. “But it didn’t have a pretty girl like you in it.”

“The freezer,” said Arild.

He the Rich One shook his head. “You can’t afford it.”

“No,” agreed Rune. “He can’t afford it.”

Arild picked up his newspaper. Then he seemed to change his mind. “You must help yourself to your purchases,” he said abruptly. “I have to show pia her museum. If you want to see her, then you must shop more often at your local near-store.” He stood and started limping toward the door. He had a bad knee, from jumping out of trucks, but at the moment his limp seemed exaggerated.

“Anyway,” called He the Rich One, “the freezer wouldn’t fit through your door frame.”

“Yes, it would.”

“No, it wouldn’t.”

“We’ll see about that,” said Arild, closing the door behind him.

Outside the clouds hung low, so that only the bases of the mountains were visible. The air was full of moisture; though it wasn’t raining, the road glistened. I followed Arild past the diesel pump—the sheep were gone—and around the barn, to a small courtyard with a flagpole. Two lambs trotted after us, bawling. Arild had discovered their mother dead the week before, the lambs curled atop her body. The sight hurt his heart. Now he fed them warm milk five times a day—a task, he said, that would soon be mine. If I wanted it.

Toward the water, white and tall, was the Old House—the heart of Mortenhals, where Arild had been born and intended to die. It rose as high as the flagpole, its walls worn but freshly painted. But if the Old House looked grand in its age, the Old Store looked simply shabby. Its walls were covered with chipped white paint, and its windows, some of them broken, papered with cardboard. Three millstones rested in the overgrown grass by the cement steps, beside an empty beer can, and the steps themselves shifted under my weight. Arild inserted a skeleton key and wrestled the knob with both hands to open the door.

We stepped into a chill. The room was grayish, all colors dulled into a narrow range of wood and metal and faded labels. I could see, through a pile of crates and boxes, how the shop had once stood: a main room with an L-shaped counter, painted green, which separated the shopkeeper from his customers. The walls behind the counter were lined with shelves, and the shelves with wares: shoes, soap, condensed milk, liquor bottles, plastic buttons, glass jars with the word Norway on them, which, Arild said proudly, were in high demand among hipsters on the Internet. From the ceiling dangled mittens, wooden ice skates, meat grinders, horseshoes, lanterns, bicycle gears, buoys, cowbells, and a copper teakettle. The effect was that of a jungle, dense with low-hanging vines, and I found myself ducking even though there was room to stand. To the right of the door, a potbellied stove wore a gold crown and a name tag that said: THE OVEN ELVIRA. The stove was not original to the shop; Arild had purchased it recently from an artist in Tromsø, and it was she who named it Elvira, and painted the crown gold.

Arild glanced at me. “It’s dirty work for a city girl.”

“I like it.” I waded over to a window and peeled off its cardboard shade, releasing a beam of light. A dead songbird lay on the windowsill. The air pulsed with dust; I waved my hand and watched ripples swirl through the room.

From a wooden box, Arild lifted a photo of

the shop as it had once been: a small white building, covered with metal signs for tobacco and cardamom. Arild still had the signs in his basement. Soon we could hang them in their original places, he said, hefting an antique riveter in one hand. “And when the time comes, we’ll use this instead of nails. One thing that’s nice is that you need a special tool to get the rivets out. That way nobody will be able to steal the signs.”

“But you know everyone,” I said. “Who would steal from the Old Store?”

Arild stared at me for a long moment. Then—“No one. Of course not.” He hummed again, louder, as he set the key at the edge of the counter. “Remember to lock the door when you leave.”

MY FIRST YEAR IN NORWAY I’d been ten years old, living with my parents in Oslo, where my father, an anti-tobacco researcher, evaluated a proposed smoking ban. I went to school in a rich part of town, but spent my days in the attic with the other outlanders—a dozen or so Pakistanis and Somalians and Russians—doing things like making cauliflower soup for those students who had no food at home. A Russian girl named Natasha became my closest friend, though we spoke no language in common; together we explored the wide clean streets of the city, took buses to the ends of their lines, ice-skated in Vigeland Park after dusk. Norway seemed like one of the safest places for little girls to be, and we took to our freedom wildly. At the time, in the late ’90s, mothers still left babies outside shops in their strollers, confident that if the infants fussed, they would be cared for by passersby.

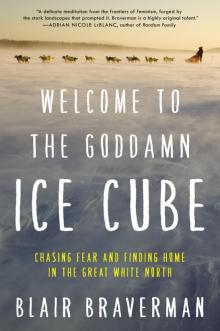

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube

Welcome to the Goddamn Ice Cube